A Summary

Compiled by Bahman Oskoui

Oil in Persia and the Bakhtiaris

Background

Petroleum seepages had been known and worked for centuries in Persia. Bitumen deposits covering the ground or gas and liquid oil seepages through cracks in the rocks have all been familiar sights in the southwest of the country. Bitumen was used by all generations, as mortar for brick laying, linings for water channels, as caulking material for shipbuilding, setting of jewels and provided fuel for lighting. Crude oil was also prized for its medicinal properties. Travelers visiting Persia in the seventeenth century had made many references to the existence of oil in the southwestern districts. W.K. Loftus report in August of 1855 to the Geological Society in London was the first official record of such finding. Loftus was a member of the Persian-Turkish Frontier Commission and had traveled extensively over the archaeological sites in the area and had noticed oil indications in the neighborhood of Masjid-e-Suleiman.

Oil seepage in South-West Persia |

Baron de Reuter

Malkom Khan, a reformist and Persian Minister in London in the 1870s, felt that for the sake of prosperity of Iran, it was necessary to introduce companies from abroad and grant them concessions to establish banks, construction of railways, operation of mines etc. It was in this spirit and perhaps for questionable personal motives, that Malkom Khan approached many companies and investors in the City of London. When all City contacts were exhausted, he turned to Baron Julius de Reuter and interested him in a seventy-year railway concession from the Caspian to the Persian Gulf. Baron de Reuter was a German who had become naturalized British subject in 1857 and had made a fortune with his news agency business. Reuter who was quite unfamiliar with Persia, sent his representative to Tehran to negotiate the details and ended up in July 1872, after putting down a deposit of 40,000 Pounds, with a grandiose concession which, in addition to the railway, gave him exclusive rights for seventy years throughout Persia for tramways, mining, irrigation, water works and exploitation of the state forests. He was also given a twenty-year monopoly over the Persian Customs and the first option on any concessions for public utilities, roads, postal services, manufacturing plants and banks.1 In return, 20% of the railway's profits and 15% of the profits of other activities undertaken by Reuter were to go to the Shah. This concession was the most complete and in the words of a French statesman, nothing of Persia was left to the Persians except the atmosphere!

The clergy and the Russians stirred up popular feeling against the surrender of the nation's birthright to foreigners. The Shah was forced to bow to the opposition and in November 1873 cancelled the concession but it was not until 1889 that Reuter was eventually offered as compensation, a new concession for banking and mining rights for sixty years. This concession led to the formation of the Imperial Bank of Persia "Bank-e-Shahi" which enjoyed huge success, and with a change of name, continued operations in Persia until 1952. Reuter had been greatly helped in reaching this satisfactory settlement by the energetic support of the British Minister in Tehran, Drummond Wolff and with help from Antoine Kitabchi, an enterprising Persian/Armenian entrepreneur and a confidant of the Prime Minister. Soon after, Reuter formed Persian Bank Mining Rights Corporation and began drilling for oil. The exploration of the concession was limited to 10 years and it would be cancelled if no production had been commenced. The Company raised a capital of 1,000,000 Pounds and the Persian Government was entitled to 16% of the net profits The Corporation drilled three wells and even at the depth of 800 feet, no oil was struck. After 10 years of fruitless search and drilling, the company folded and in 1899 the Government announced the cancellation of Reuter's oil rights.

The clergy and the Russians stirred up popular feeling against the surrender of the nation's birthright to foreigners. The Shah was forced to bow to the opposition and in November 1873 cancelled the concession but it was not until 1889 that Reuter was eventually offered as compensation, a new concession for banking and mining rights for sixty years. This concession led to the formation of the Imperial Bank of Persia "Bank-e-Shahi" which enjoyed huge success, and with a change of name, continued operations in Persia until 1952. Reuter had been greatly helped in reaching this satisfactory settlement by the energetic support of the British Minister in Tehran, Drummond Wolff and with help from Antoine Kitabchi, an enterprising Persian/Armenian entrepreneur and a confidant of the Prime Minister. Soon after, Reuter formed Persian Bank Mining Rights Corporation and began drilling for oil. The exploration of the concession was limited to 10 years and it would be cancelled if no production had been commenced. The Company raised a capital of 1,000,000 Pounds and the Persian Government was entitled to 16% of the net profits The Corporation drilled three wells and even at the depth of 800 feet, no oil was struck. After 10 years of fruitless search and drilling, the company folded and in 1899 the Government announced the cancellation of Reuter's oil rights.

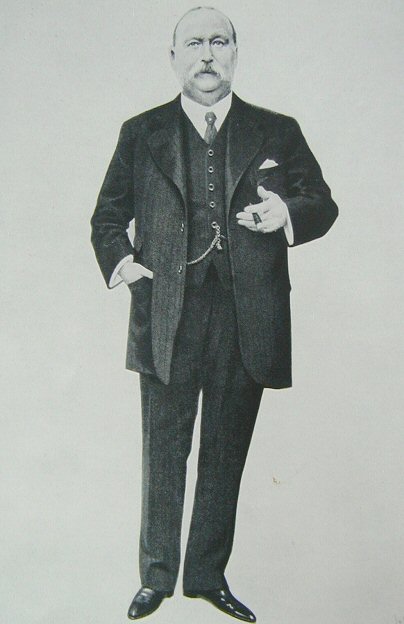

William D'Arcy

It was in 1900 that William D'Arcy appeared on the oil scene. D'Arcy was a British solicitor practicing in Australia who had made a fortune investing in a gold mine. He had invested in "Mount Morgan Mine", the richest gold mine in Australia in the 1880's, belonging to one of his clients. In exchange for some capital infusion (500 Pounds) and his work as organizer, D'Arcy took one third of the capital stock of 1 million Pounds. By 1886 each share was worth 17 Pounds Sterling and it was towards the end of the century that D'Arcy returned to England a millionaire and retired to a life of luxury in London.2 His elegant house in Grosvenor Square was the setting for many lavish parties including birthday parties given for Mrs. D'Arcy in which the Great Caruso would sing and entertain the guests. D'Arcy was however getting more restless and bored and was constantly looking for new and exciting projects to occupy his time and endless mental energy.

William Knox D'Arcy |

A few years later in Paris, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, who was recovering from a mental breakdown that ended his career as the British Minister in Tehran was approached by an old acquaintance of his Tehran days, the Armenian customs official, Antoine Kitabchi who now held a temporary post as the Persian Commissioner-General at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Kitabchi talked to Wolff and asked him, in return for a suitable commission, to find a rich buyer for the now defunct Reuter's oil concession. Kitabchi and Wolff began a search for European capital to take over the concession for oil now that Reuter's had expired. The City of London's investors were not interested in getting involved in any further business ventures in Persia as their fingers had been badly burned with the cancellation of the Tobacco Concession and the failure of Reuter's Persian Bank Mining Rights Corporation. They had also been badly hurt financially when they were caught in a non-existent National Lottery Concession swindle orchestrated by Malkom Khan, the Persian envoy in London. Drummond Wolff and Kitabgi were also concerned that the concession should remain in British hands and not to go to the Russians. The case for finding oil had further been strengthened by Jacques de Morgan, the famed French archaeologist who had seen many oil seepages during his wanderings in Persia and had published a preliminary geological article in "Annales des Mines" in 1892. Gulbenkian (Mr. 5 percent) had already been approached but he had rejected the proposal after inspecting the prospectus calling it "a very wild cat" and a business for a gambler. Wolff thought of D'Arcy, now settled in England with money to burn who also happened to be in Paris for the exposition. A meeting was arranged between the three men and D'Arcy agreed to study the proposal and the terms of the draft concession3, after he read the report of findings of the French archaeologist, Jacque de Morgan.4 The experience he had acquired through Mount Morgan Gold Mining Company had provided the optimism and confidence to tackle anything. Seeing the name of "Morgan" once again was taken as good omen. Fired with enthusiasm, D'Arcy agreed to look into the matter seriously and sent out geologists to Persia to explore.

The Oil Concession

D'Arcy's geologist and his team found the two ends of a 500 miles oil field and reported this to London. In 1901 D'Arcy sure of his ground, dispatched his confidential advisor and agent, Alfred Marriott to Tehran for negotiations. Marriott was a very astute and clever negotiator and it was on the 28th of May 1901 that in the convenient absence of the Russian envoy on a hunting trip, he succeeded in securing an all-important concession for the exploitation of natural gas, petroleum and asphalt in the whole of Persia, except for the five northern provinces, for a period of sixty years; also to construct pipelines from anywhere in Persia to the Persian Gulf. This concession was obtained with the help of Atabak, the powerful Prime Minister who had paid a recent visit to D'Arcy during his latest trip to England and was introduced to him by Sir Henry Drummond Wolff.5 There are some accounts of Marriott having paid 20,000 Pounds cash to Nasser-al-Din Shah through the good offices of Atabak in order to obtain the Shah's approval for the Agreement. He furthered promised that the Persian Government would receive 20,000 of the One Pound Sterling shares in the company that D'Arcy was about to form and 16% of the net profits.

Beginning Explorations

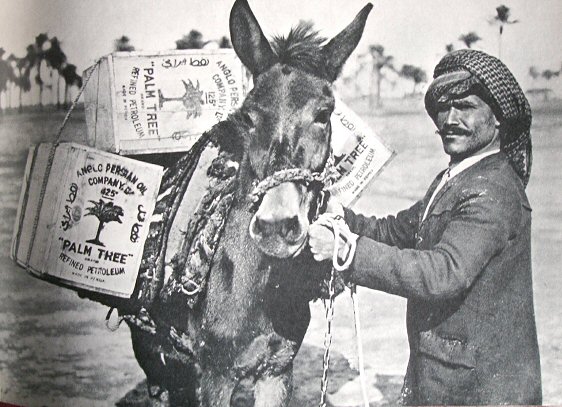

Subsequent to securing the exclusive exploitation concession, a camp was set up in the Maidan-e-Naftoon. Nearby were the ruins of Masjid-e-Soleiman, the Temple of Solomon. To the eternal fires of this shrine the oil had been fed in the days of the Zoroastrians.6 Supplies had to be carried on donkeys and mules over treacherous roads, no port facilities existed, no adequate roads, and pipes had to be laid over mountainous territories. D'Arcy dispatched G.B. Reynolds, an able Englishman to Iran to manage the operation. Reynolds, an engineer, had experience in drilling for oil in Sumatra and was accustomed to harsh environments. He had also dispatched a team comprising of Canadian and Polish drillers, an American engineer, an Indian doctor and was utilizing the labour force of Bakhtiari tribesmen who had never before handled any sort of machinery. The team struggled in the harsh terrain with high hopes. Meanwhile D'Arcy realized that he had to set up a syndicate to guarantee the financial backing for the Concession, as he could not sustain the expenses on his own. D'Arcy took advice from lawyers and registered the "First Exploitation Company" on the 21st of May 1905 with a capital of 600,000 Pounds and transferred all his rights and privileges of his Concession to the Company in return for 350,000 shares of 1 Pound each. The Company was also authorized to pay the Persian Government 16 per cent of its annual net profits.

D'Arcy's efforts in finding oil in Persia was a drain on his capital and seeked new investors with the help of the British Admiralty who had invested 100,000 pounds. He had already spent 200,000 Pounds of his own money. Even though D'Arcy never set eyes on Persia, he was confident that he would find oil if he could persevere. D'Arcy prevailed and continued tirelessly. His efforts eventually paid off .The discovery marked a turning point in Persian history as well as the history of the Middle East. The credit goes largely to two Englishmen-William D'Arcy who risked all and persevered, and to G.B. Reynolds who was in charge of the operation in Persia. Without William D'Arcy, Britain could not have achieved an independent supply of oil for her navy during the 1st World War.7

D'Arcy's efforts in finding oil in Persia was a drain on his capital and seeked new investors with the help of the British Admiralty who had invested 100,000 pounds. He had already spent 200,000 Pounds of his own money. Even though D'Arcy never set eyes on Persia, he was confident that he would find oil if he could persevere. D'Arcy prevailed and continued tirelessly. His efforts eventually paid off .The discovery marked a turning point in Persian history as well as the history of the Middle East. The credit goes largely to two Englishmen-William D'Arcy who risked all and persevered, and to G.B. Reynolds who was in charge of the operation in Persia. Without William D'Arcy, Britain could not have achieved an independent supply of oil for her navy during the 1st World War.7

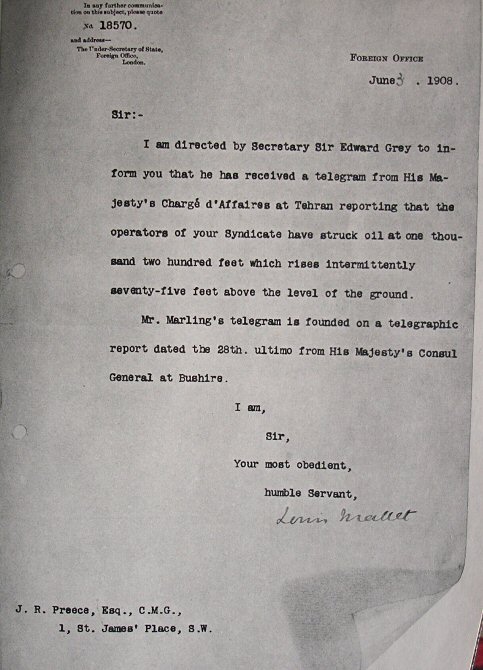

News of Success |

The Agreement with Bakhtiari Chiefs

Before the explorations could begin, drilling permission had to be obtained from the Bakhtiari khans in whose territory all the oil deposits lay. Reynolds received much needed help from the British Consul in Isfahan, John Preece in negotiating with the Bakhtiaris. These negotiations were interrupted with the death of Esfandiar khan in 1903 and later resumed with other chiefs and in particular with Sardar Jang Bakhtiari.

An agreement was eventually reached between the explorers and four Bakhtiari leaders; two from Ilkhani and two from Haj Ilkhani branches as was customary. The Ilkhani signatories were Najaf Gholi khan (Samsam Saltaneh) and Haj Ali Gholi khan (Sardar Asad the 2nd). The Haj Ilkhani signatories were Sardar Jang and Sardar Mohtashem. The agreement was signed much to the objections of the central government in Tehran. Much credit goes to John Preece for his negotiating skills especially in negotiations with Sardar Asad. Reynold had met John Preece in London and it had been agreed by the Foreign Office that Preece should lend a hand in negotiations with the Khans with whom he had a long relationship. On 13 October 1905, Reynold traveled to Shalamzar, the residence of Samsam Saltaneh who was then the Ilkhani, joined by Preece three days later.

Negotiations with the four leading Bakhtiari Khans took place on the 16th and 19th of October 1905, and as Reynolds describes it, "in all of which Sardar Asad, Hadji Ali Gholi Khan took, I may say the entire role as spokesmen of the Chiefs, no other chief having it seemed a word to say in his presence…He, I should say, was masterful and has seen more of the world than most Khans, and has a greater flow of language, so it may have been a pre-arranged affair that he should hold the platform." 8

Sardar Asad was insisting in demanding 5 percent of the share capital of each working company formed. After further discussions and meetings, Preece persuade the Khan to accept 3 per cent of all shares issued but no agreement had yet been reached on the guarding arrangements for which 2,000 Pounds per year had been offered irrespective of the number of drilling camps which was later agreed not to be more than four camps. Following the insistence of the Il-khani (Samsam Saltaneh) and Shahab-al-Saltaneh, the Il-bagi, Sardar Asad also signed the agreement. The last signatory was Sardar Jang who also signed. The general terms of this agreement reached on 15 November 1905 were as follows:9

An agreement was eventually reached between the explorers and four Bakhtiari leaders; two from Ilkhani and two from Haj Ilkhani branches as was customary. The Ilkhani signatories were Najaf Gholi khan (Samsam Saltaneh) and Haj Ali Gholi khan (Sardar Asad the 2nd). The Haj Ilkhani signatories were Sardar Jang and Sardar Mohtashem. The agreement was signed much to the objections of the central government in Tehran. Much credit goes to John Preece for his negotiating skills especially in negotiations with Sardar Asad. Reynold had met John Preece in London and it had been agreed by the Foreign Office that Preece should lend a hand in negotiations with the Khans with whom he had a long relationship. On 13 October 1905, Reynold traveled to Shalamzar, the residence of Samsam Saltaneh who was then the Ilkhani, joined by Preece three days later.

Negotiations with the four leading Bakhtiari Khans took place on the 16th and 19th of October 1905, and as Reynolds describes it, "in all of which Sardar Asad, Hadji Ali Gholi Khan took, I may say the entire role as spokesmen of the Chiefs, no other chief having it seemed a word to say in his presence…He, I should say, was masterful and has seen more of the world than most Khans, and has a greater flow of language, so it may have been a pre-arranged affair that he should hold the platform." 8

Sardar Asad was insisting in demanding 5 percent of the share capital of each working company formed. After further discussions and meetings, Preece persuade the Khan to accept 3 per cent of all shares issued but no agreement had yet been reached on the guarding arrangements for which 2,000 Pounds per year had been offered irrespective of the number of drilling camps which was later agreed not to be more than four camps. Following the insistence of the Il-khani (Samsam Saltaneh) and Shahab-al-Saltaneh, the Il-bagi, Sardar Asad also signed the agreement. The last signatory was Sardar Jang who also signed. The general terms of this agreement reached on 15 November 1905 were as follows:9

1. The Agreement was to remain in force for 5 years. All required land was to be handed over by the Khans "at the fair price of the day". Non-arable land was to be free.Article 1 of the Agreement later became the subject of serious dispute between the Company and the Khans. Dr. Young representing the Company, negotiated during 17-28 April 1911 with Sardar Mohtashem and Sardar Bahador at Masjid-e-Suleiman and offered the Khans 23 Tumans a jarib (a third of an acre) for cultivated land and 5 Tumans for hill tracts. The Khans agreed taking 2,000 Pounds as negotiators and two installments of 10,000 Pounds and 5,000 Pounds, which with a 5,000 Pounds advance they had received the previous year, made up the agreed sum thus concluding the dispute after 6 years of negotiations.

2. The Company was to pay the Khans 2,000 Pounds per annum (subsequently increased to 2,500 Pounds) in quarterly installments, in return for the guards furnished by the latter. …. Before the finding of oil, the Khans were to furnish two bodies of guards to protect the two places where drilling was to be done. After the finding of oil, the Khans were to furnish as many bodies of guards as would be required to protect the various spots where drilling would be carried out.

3. In the event of sufficient oil being found in Bakhtiari territory, the terms of the Agreement were to remain binding as long as the D'Arcy Concession continued in force.

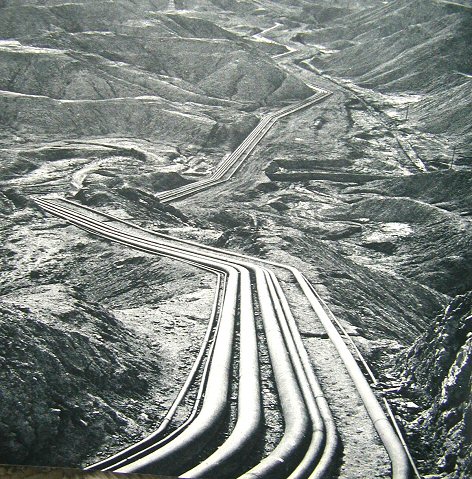

4. On the pipeline being constructed, the Company was to increase the guarding subsidy to 3,000 Pounds per annum.

5. After the formation of one or more companies to work oil in the Bakhtiari country, and after oil had been passed through the pipeline, the Company was to grant the Khans 3 per cent of all the ordinary shares issued by such company or companies, the said shares to be fully paid.

6. Should the employees of the Khans fail in their duties, the Company would have the right to ask for compensation for any loss.

7. On the expiration of the D'Arcy Concession, all buildings that belonged to the Company were to become the property of the Khans.

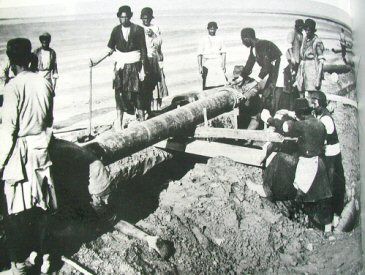

Oil pipeline through Bakhtiary territory |

The agreement over oil and protection of the pipeline was the second serious contact between the British and the Bakhtiari leaders. The first being the agreement in respect to the Lynch road. Previously, there had been only sporadic contact between the British and the Bakhtiaris. Sir Henry Rawlinson spent time amongst them in 1835 to suppress an uprising, and Sir Henry Layard had spent 10 adventurous months amongst them. However, towards the end of the 19th century, the British in order to compete with the Russian/Persian trade, saw an opportunity in opening the Karun river to merchant shipping and an enterprising young man based in Isfahan by the name of George Mackenzie10 had recognized that the best route for bringing British goods into Iran was through Karun River. He had concluded that a road from Ahwaz to Isfahan, right through the heartland of the Bakhtiaris could be constructed. John Preece, the British Consul in Isfahan helped a British firm, Lynch Brothers reach agreement with the Bakhtiary khans for the construction of a 270-mile long "Lynch" road linking these two cities. Though the road they built was basically a mule track, the engineering and logistic problems were quite considerable. Men and mules were utilized to carry heavy steel girders for the bridges high up in the mountains. Offices were opened in Ahwaz and Shushtar where local products like sesame seed and wool were stored and caravans would be assembled for their two-week journey to Isfahan.

The Bakhtiaris and the British enjoyed a special relationship that was not always smooth. As can be seen from negotiations over oil, contrary to the opinion of a few, Bakhtiaris did not need the British nor did they blindly agree to the British wishes and demands. On the contrary, it was the British who desperately needed the support and friendship of the Khans in order to safeguard their vital interests in that region; a support that they did not always get. Even during the march of the Bakhtiaris to Tehran in the Constitutional movement, the British tried their best to prevent their participation but of no avail. The relationship began to sour during the First World War when some of the Bakhtiaris notably Bibi Maryam a daughter of the Ilkhani, took a hard pro-German stand against the British. She was followed by several of the younger Khans some of whom were supporters of Moslem Ottomans due to religious reasons. After the War and the orchestration of bringing Reza Khan to Power, the British decided to back Reza Shah's efforts to centralize affairs of the tribes and weakening of their autonomy. The British therefore did not intervene to save the Khans from persecution thus putting the myth of Bakhtiari/British "special" relationship to rest for good.

The Bakhtiaris and the British enjoyed a special relationship that was not always smooth. As can be seen from negotiations over oil, contrary to the opinion of a few, Bakhtiaris did not need the British nor did they blindly agree to the British wishes and demands. On the contrary, it was the British who desperately needed the support and friendship of the Khans in order to safeguard their vital interests in that region; a support that they did not always get. Even during the march of the Bakhtiaris to Tehran in the Constitutional movement, the British tried their best to prevent their participation but of no avail. The relationship began to sour during the First World War when some of the Bakhtiaris notably Bibi Maryam a daughter of the Ilkhani, took a hard pro-German stand against the British. She was followed by several of the younger Khans some of whom were supporters of Moslem Ottomans due to religious reasons. After the War and the orchestration of bringing Reza Khan to Power, the British decided to back Reza Shah's efforts to centralize affairs of the tribes and weakening of their autonomy. The British therefore did not intervene to save the Khans from persecution thus putting the myth of Bakhtiari/British "special" relationship to rest for good.

Discovery of oil

Meanwhile, D'Arcy was getting anxious at the speed that his capital was getting depleted and yet no oil was found in commercial quantities. He began negotiations with Burma Oil Company and the British Government in addition to private investors in order to sustain his operations. Reynold's perseverance paid off. On the 16th of May 1908, drillers working at Masjid-I-Sulleiman detected a "strong smell of gas" in the well. At 4 o'clock in the morning of May 26th, oil was struck and it was in commercial quantities. This, without question was the tip of a vast reservoir that lay beneath that barren land deep in the winter grazing grounds of the Bakhtiaris. Between the start of D'Arcy's exploration and striking oil, 7 agonizing years of patience and impatience; hopes raised and dashed; thirst, hunger, dehydration and heat strokes had passed. Reynolds wrote in his telegraph to London: "I have the honour to report, that this morning at 4 a.m. oil was struck in the No. 1 hole at a depth of 1180 feet…." The discovery of oil in commercial quantity was a milestone and a turning point in the history of Persia. It also brought the Bakhtiaris and the British close together out of necessity and mutual goals, an association that the central government in Tehran eyed with great suspicion.

Formation of Anglo-Persian Oil Company

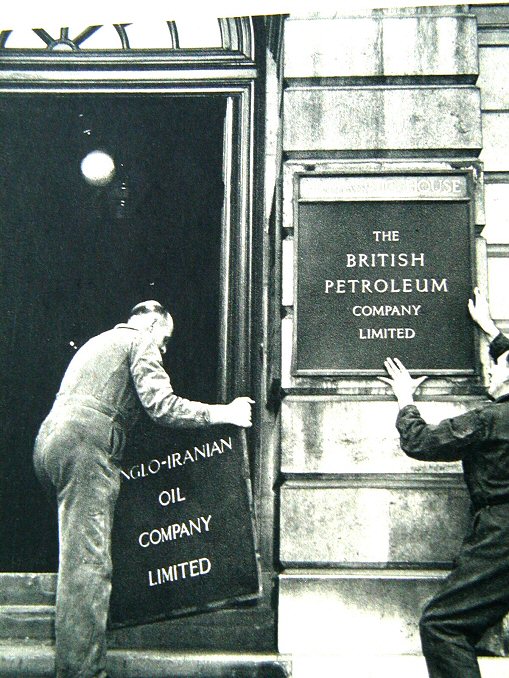

On the 14th of April 1909 the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was formed with an initial capital of 2 Million Pounds. At the Admiralty's suggestion, a highly respected public figure, the eighty-nine year-old Lord Strathcona, accepted the post of Chairman with D'Arcy as a director until his death in 1917. The new company created tremendous public interest in Britain. Burmah Oil provided all its initial capital except a small amount subscribed by Lord Strathcona. D'Arcy however did not go un-rewarded. He was reimbursed in cash for all he had spent, and was given shares in Burmah Oil valued at that time at 900,000 Pounds Sterling11. The Admiralty had seen the importance of oil as fuel for the Navy and to investigate the fields and the reserves they held, the British Government dispatched professor John Cadman the greatest oil expert at that time, to Persia to investigate. Upon receiving Cadman's report, Lord Fisher of the Admiralty with the help from Winston Churchill, a Member of Parliament, persuaded the British Parliament to permit the Government to purchase 51% of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company in 1912. Whitehall then put a director on the Board with veto powers. The British fleet was shortly afterwards converted to oil from coal.

Bakhtiari Oil Company

The British had realized that close relationship with the Bakhtiari Khans was the key to their success in the oil territories and that to this aim, three steps had to be taken. One, was to have an agreement for the purchase of territories as needed. Two, an agreement for the protection of installation and the pipelines and the third, was to make the Bakhtiaris partners in the Company. The first two had been achieved. On the 13th of April 1909, Bakhtiari Oil Company was formed with a capital of 400,000 Pounds, and it was agreed that the Bakhtiari khans were to receive 3% of the profits of companies formed in addition to holding 37,200 shares of the First Exploitation Company and 11,670 shares of the Bakhtiari Oil Company. With the formation of Anglo-Persian Oil Company Ltd., all the rights were transferred to the new parent company.

The Khans had received substantial sums in dividends and loans from the A.P.O.C. According to a report received by Mr. Teymourtach, Minister of Court of Reza Shah from special envoy, Mirza Eissa Khan Fayz dated 10th January 1929; the Bakhtiari leaders of both Ilkhani and Haj-Ilkhani families had borrowed substantially from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and had put up their shares of stock as collateral. In 1922 they had borrowed 114,000 Pounds at 4%, and again 30,000 Pounds in 1926 at 5% interest. These sums were in addition to receiving regular dividends and other previous borrowing. All together, the Bakhtiaris had borrowed a hefty sum of 382,633 Pounds from 1913 to 1928.12 This borrowing suited the British because by holding the stocks as collateral, the Bakhtiari leaders would remain shareholders and motivated in safeguarding the interests of the Company in the region. In his report number 28/1 dated 28 December 1928, Fayz writes:

"that sons of Emam Gholi Khan Haj Ilkhani and Hossein Gholi Khan Ilkhani in total own 37,320 shares of 1 Pound nominal value in the First Exploitation Company." He also adds: The amounts paid to the Khans as dividend net of the interest on amounts already borrowed from the Company, is 124,214 Pounds Sterling covering the period of 1913 to 1919 inclusive. This was in addition to the above-mentioned loans of 382,633 Pounds during the same period.13 The division of shares was 5 parts to the sons of Ilkhani and eight parts to the sons of Haj Ilkhani. There is no record of the repayment of the loans.

The Khans had received substantial sums in dividends and loans from the A.P.O.C. According to a report received by Mr. Teymourtach, Minister of Court of Reza Shah from special envoy, Mirza Eissa Khan Fayz dated 10th January 1929; the Bakhtiari leaders of both Ilkhani and Haj-Ilkhani families had borrowed substantially from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and had put up their shares of stock as collateral. In 1922 they had borrowed 114,000 Pounds at 4%, and again 30,000 Pounds in 1926 at 5% interest. These sums were in addition to receiving regular dividends and other previous borrowing. All together, the Bakhtiaris had borrowed a hefty sum of 382,633 Pounds from 1913 to 1928.12 This borrowing suited the British because by holding the stocks as collateral, the Bakhtiari leaders would remain shareholders and motivated in safeguarding the interests of the Company in the region. In his report number 28/1 dated 28 December 1928, Fayz writes:

"that sons of Emam Gholi Khan Haj Ilkhani and Hossein Gholi Khan Ilkhani in total own 37,320 shares of 1 Pound nominal value in the First Exploitation Company." He also adds: The amounts paid to the Khans as dividend net of the interest on amounts already borrowed from the Company, is 124,214 Pounds Sterling covering the period of 1913 to 1919 inclusive. This was in addition to the above-mentioned loans of 382,633 Pounds during the same period.13 The division of shares was 5 parts to the sons of Ilkhani and eight parts to the sons of Haj Ilkhani. There is no record of the repayment of the loans.

Reza Shah and sale of Bakhtiari shares

With Reza Shah's ascent to power, the autonomy of Bakhtiaris began to diminish. Reza Shah was intent on reducing the power of the Chiefs at first through military action and second, through economic and political reorganization of territories and arrest of its leaders. The incident at the Shalil Pass on 30 July 1922, in which the Bakhtiaris had ambushed a column of 400 government soldiers en route to Khuzistan, was the beginning of clamp down. The khans had decided that if they let the soldiers get through, then this would give the impression that the Bakhtiaris had capitulated. The decision was therefore reached to resist and stop the column. Bakhtiari fighters closed the passes. Fighting broke out and scores of Government soldiers were killed and scores taken prisoner with guns and ammunition falling into the hands of the Bakhtiaris. Several of the Khans were implicated in the decision to attack the soldiers especially Sardar Fateh and Sardar Eghbal14. At that time Reza Khan was the Minister of War and had not yet consolidated his power and authority but he never forgot this event and waited patiently to avenge the defeat of his soldiers. He did however settled on 150,000 Tumans of restitution paid by the Khans15. In 1928 Anglo-Persian Oil Company was ordered to negotiate with the Governor of Khuzistan for any land acquisitions instead of direct purchase from the Khans. On the 29th of November 1933 Reza Shah ordered that Sardar Asad the 3rd, his close friend and Minister of War be imprisoned. Four months later on the 30th of March 1934, he was murdered in his jail cell. Even now after almost 70 years, no one knows the reason for his arrest and death. Many other leaders of various tribes including the Bakhtiaris were subsequently arrested and put on trial by a military court. Sardar Fateh (father of Shapour Bakhtiar) and Sardar Eghbal were amongst the 12 tribal chiefs and Kalantars of various tribes that were executed by firing squad. These two Sardars were involved in a rebellion led by Ali Mardan Khan of Chahar Lang in the battle of Sefid Dasht. Several other Bakhtiari Khans were sentenced to various prison terms. Amir Jang for example, spent 7 years in prison and was freed after the abdication of Reza Shah. Khan-Baba Khan Asad also died in prison under torture. Bakhtiari territory was divided up between the provinces of Isfahan and Khuzistan. In 1933, the positions and titles of Ilkhani and Ilbagi were abolished and Morteza Gholi Khan Samsam, who was at the time the Ilkhani, became Governor of Bakhtiari. The final blow came in 1938-1939 when the Chiefs were ordered to sell their shares in the Company to the central government subsequent to the cancellation of D'Arcy Concession. Each of the descendents of Ilkhani and Haj Ilkhani received 115,000 Tumans. The Bakhtiari chiefs were also ordered to make available to the Government inspectors, lists of their properties and land in the Bakhtiari territory in order to be exchanged with similar properties in other provinces.

Grievances and Claim against the Central Government

When Soraya Esfandiary became Queen, Bakhtiaris led by Amir Hossein Khan (Ilkhan Zafar), his sister, Forough Zafar and Khalil Khan Esfandiari (Queen Soraya's father), saw an opportunity to reclaim their shares and declare the prior sale agreement as null and void on the grounds that Morteza Gholi Khan (Samsam Bakhtiari), who was one of the principal signatories to the sale agreement, did not have any shares of his own to sell and his signature was obtained under duress. He had in fact four years earlier, divided all his assets amongst his children. The case was taken to court and the government lost. Both parties then decided to take the case to arbitration and eventually agreed on a settlement whereby representatives of each branch namely Ilkhani and Haj Ilkhani would in total receive 7 Million Tumans (in excess of $1,000,000 at the time) and forfeit any future claims.16

[1] "The English Amongst the Persians" by Denis Wright, London 1977

[2] Evening Standard, London, December 1, 1932

[3] The English Amongst the Persians. Sir Denis Wright

[4] Oil in the Middle East by S.H. Longrigg.London 1954

[5] William Knox D'Arcy, Australian Gold and Persian Oil. By Margaret Carnegie

[6] Evening Standard, London, December 1, 1932

[7] William Knox D'Arcy by Margaret Carnegie. Melbourne 1992

[8] The History of British Petroleum Co. Volume 1. By R.W. Ferrier

[9] ibid

[10] Later on partner of the transport firm of Grey Mackenzie

[11] "Adventure in Oil, The Story of British Petroleum" by Henry Longhurst

[12] Oil During Reza Shah's Reign. Published in 1999 by the office of the President.

[13] ibid

[14] Sardar Zafar in his memoirs refers to this incident but does not mention the direct involvement of the two Chiefs.

[15] Memoirs of Sardar Asad Bakhtiari

[16] Memoirs of Amir Bahman Khan Samsam (son of Morteza Gholi Khan)

[2] Evening Standard, London, December 1, 1932

[3] The English Amongst the Persians. Sir Denis Wright

[4] Oil in the Middle East by S.H. Longrigg.London 1954

[5] William Knox D'Arcy, Australian Gold and Persian Oil. By Margaret Carnegie

[6] Evening Standard, London, December 1, 1932

[7] William Knox D'Arcy by Margaret Carnegie. Melbourne 1992

[8] The History of British Petroleum Co. Volume 1. By R.W. Ferrier

[9] ibid

[10] Later on partner of the transport firm of Grey Mackenzie

[11] "Adventure in Oil, The Story of British Petroleum" by Henry Longhurst

[12] Oil During Reza Shah's Reign. Published in 1999 by the office of the President.

[13] ibid

[14] Sardar Zafar in his memoirs refers to this incident but does not mention the direct involvement of the two Chiefs.

[15] Memoirs of Sardar Asad Bakhtiari

[16] Memoirs of Amir Bahman Khan Samsam (son of Morteza Gholi Khan)

Distribution of Anglo-Persian kerosene (Naft-e Irani) |

|||

Unloading a boiler by hand |

Bakhtiari workers laying oil pipeline for Anglo-Persian Oil Co. |

||

British Petroleum as successor to A.I.O.C. From: BP 50 years in Pictures |

|||